Recently I scribbled a few thoughts on the contrast between Robert Greene’s teachings on “seduction, charm, deception, and subtle strategy” and William the Marshal’s example of frankness, generosity, and loyalty.

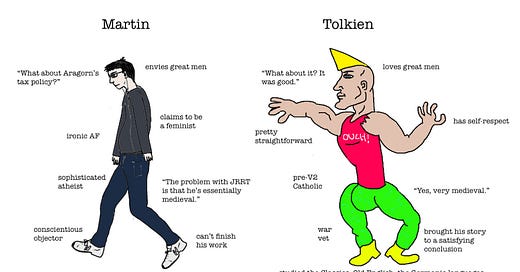

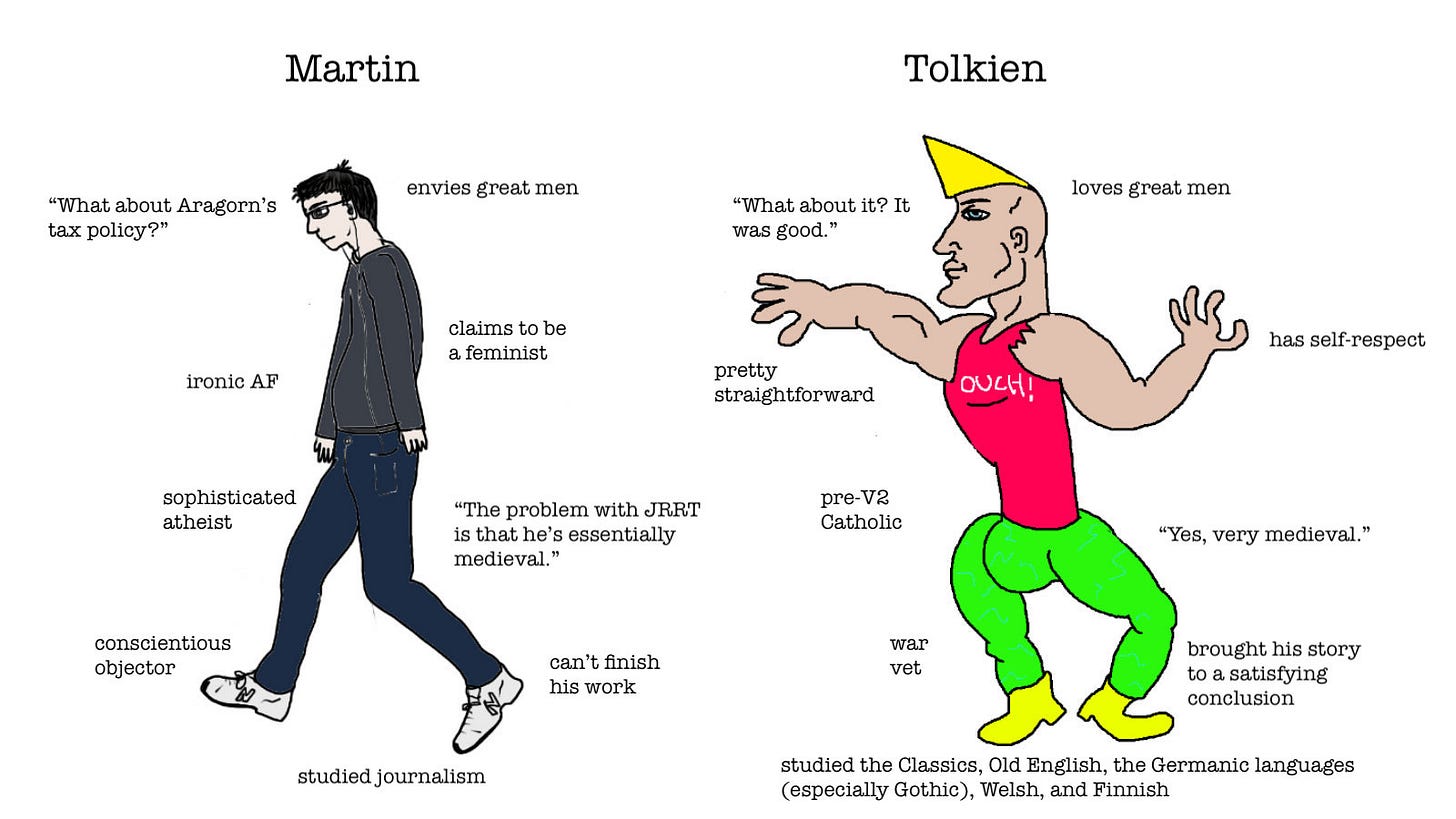

I couldn’t help but note how well a similar virgin vs. chad meme (weak, resentful, falsely sophisticated vs. simpler, stronger, unapologetic) a…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Chivalry Guild Letters to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.