“Everything happens for a reason”: this line always sounded trite to me. Instead of consolation after a setback or disaster, the words usually had the opposite effect of angering me. I was dumb and moody and melodramatic, and the last thing I wanted to hear after getting roughed up by life was that it was actually good to suffer defeat and disappointment—with no explanation of why or how it was good, just a breezy assurance. The Cult of Positive Attitude, along with Greeting Card Christianity, never helped but instead drove me into the loving arms of my favorite emo bands. I found a lot more comfort in brooding along with Taking Back Sunday.

It’s only when you hear about a life in which suffering served a purpose, preparing a man for big things, that the words might mean something.

Three men come to mind when I think of this lesson: the son of an Old Testament patriarch, a missionary, and a legendary defender of Christendom.

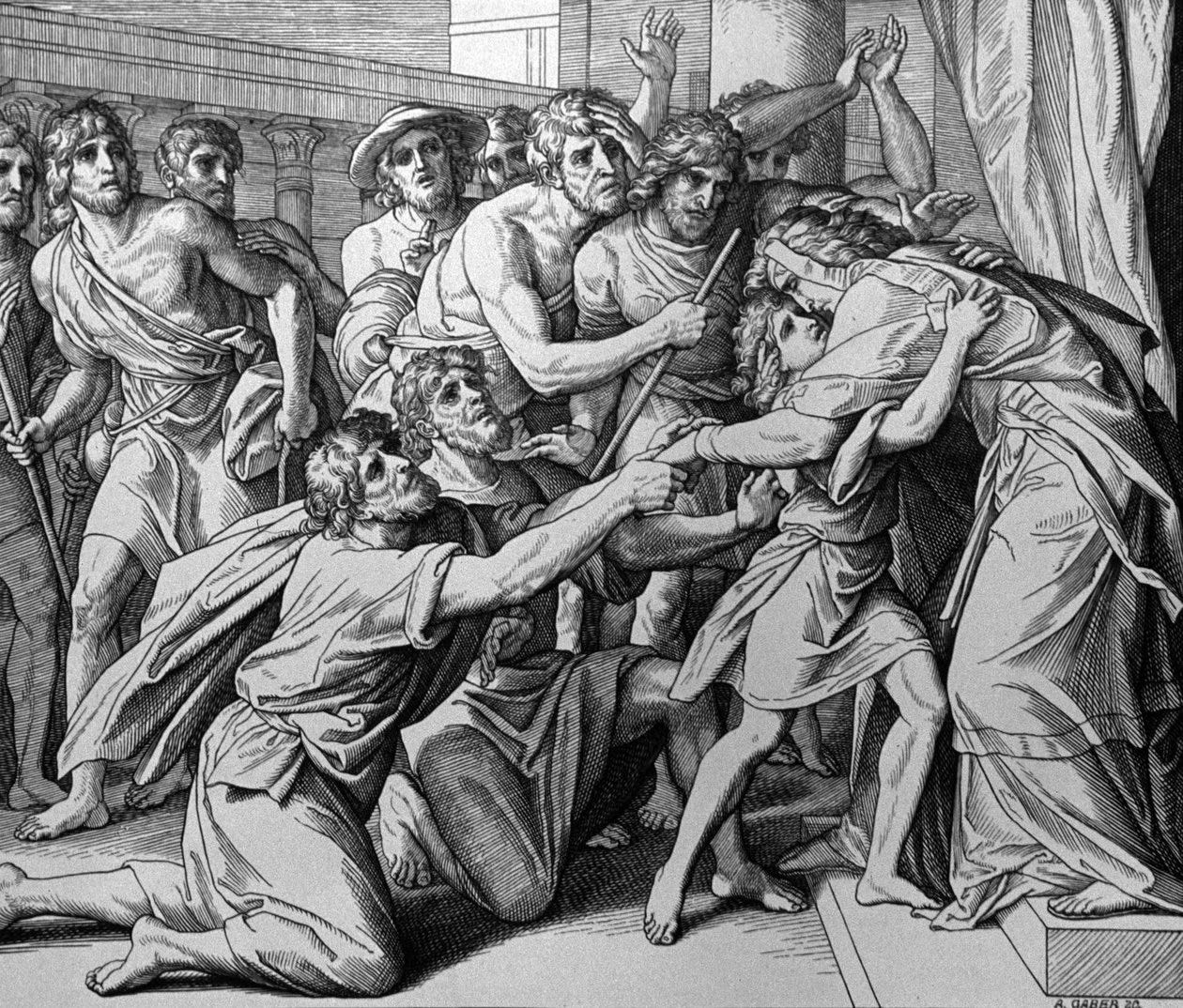

Most people should know Joseph’s story of suffering. It was bad enough that his own brothers sold him to Ishmaelite merchants and slave-traders—but bad turned to worse when his master’s lustful wife charged Joseph with “insulting” her. At that point the young man found himself in an Egyptian prison. But “the Lord was with Joseph.” In prison he had the opportunity to aid a man who would one day introduce him to Pharaoh, who in turn would need Joseph’s aid. The winding route of destiny had brought Joseph to a position of influence and given him a chance to save countless masses from starvation in an upcoming famine that would afflict the land. That includes saving his own family. Those same brothers who had sold him into slavery would come to Joseph begging to buy some of the grain that he had convinced Pharaoh to store up. The Israelites survived as a result.

Had Joseph lived a normal and happy life, he and his family likely would have died when the famine came. “You meant evil against me,” he told his brothers, “but God meant it for good, to bring it about that many people should be kept alive, as they are today.”

The life of St Patrick traces a similar course. At age fourteen this Roman Brit was abducted by pirates and taken to Ireland as a slave. He spent six years living the nightmare. Then one day Patrick heard the call of an angel telling him to run away to a ship on the coast that would take him back home. So he trekked 200 miles, got on board, and finally returned.

I have a hard time imagining the pain he endured—not just the physical pain, the loneliness, and the heartbreak of being taken from your home, but also the pain of losing those crucial formative years. What possible meaning could be found in such suffering?

For one, Patrick learned the language and culture of the people of that island. This might seem like an insignificant recompense for six years, but the knowledge made Patrick uniquely qualified to serve as God’s messenger to Ireland. In ways he couldn’t have understood, Patrick’s suffering prepared him for a grand destiny. The men he converted upon his return to Ireland would preserve the Faith after the fall of the Western Roman Empire and then bring it back to the continent when the time was right. The course of history is altered thanks to Patrick’s suffering.

A few months back I wrote an essay about George Castrioti, also known as Scanderbeg—the Albanian hero who deserves a place of honor among the greatest men to ever pick up a sword in defense of Christendom. Historian George Armstrong noted that “The exploits even of the renowned paladins of the Crusades, whether Godfrey or Tancred or Richard or Raymond, pale to insignificance by similar comparison.”

And all the honor Scanderbeg won was preceded by a suffering that almost breaks the imagination. At the age of eight, he was given over to the Ottoman Turks as a hostage to insure the good behavior of his father. He was essentially a janissary: taken as a boy, broken, indoctrinated, abused in every way, converted to Islam, and trained to be a killer of his own people. But the training and brainwashing did not take. Scanderbeg bided his time for three decades before escaping back to Albania with 300 loyal janissaries, reclaiming his birthright, and launching a legendary twenty-five-year campaign against the Ottomans in which he reportedly killed 3000 Turks by his own hand.

What’s wild is to think that his campaign might not have been possible if not for the darkness of the three decades with the Turks. Scanderbeg learned all about his enemy, was trained by them, understood their methods—and maybe more importantly, understood the importance of fighting them. His position as a general in the Ottoman army gave him a unique opportunity to take back his father’s lands and energize and unite the unruly nobles of Albania in a way otherwise not possible.

Though Albania would eventually fall to the Ottomans after the hero’s death, Scanderbeg’s defense of his own country was a major reason why Mehmed the Conqueror wasn’t able to subdue Italy and bang on the door of Western Europe. Those battles that Scanderbeg fought and won mattered. Near the end of Marin Barleti’s 16th century biography of Scanderbeg, the Archbishop of Duras reminds Scanderbeg, “I have oftentimes heard thee say that only for the defense and preservation of the [faith of Christ] thou didst think thyself to be created and to be born into this world.” Few men have ever had better grounds on which to make such a claim.

Stories like these give badly needed weight to a line like “Everything happens for a reason” or “The Lord works in mysterious ways.” They also add a note of wholesome tough love. Which is: better men than you have suffered worse, far worse—and been ennobled by it.

God allowed these trials to befall Joseph, Patrick, and Scanderbeg because he knew the young men could take the pain and because the difficulties endured would create otherwise unthinkable possibilities. The trouble is that our spiritual enemies aim to convince us otherwise. They want us to think our own suffering is meaningless, to resent it, to resent God for it—and this doubt has a self-fulfilling guarantee to it. In doubting our suffering we frustrate the potential upsides. I am convinced that this trust in Providence is the central challenge of the life of faith.

A lifetime’s worth of wisdom in this one paragraph:

Stories like these give badly needed weight to a line like “Everything happens for a reason” or “The Lord works in mysterious ways.” They also add a note of wholesome tough love. Which is: better men than you have suffered worse, far worse—and been ennobled by it.

Your best post to date, imho.

Revelation