A little flak recently came my way when I questioned Christopher Rufo’s advice to young men: “You should be listening to Dave Ramsey, not Andrew Tate.” Really I don’t think young men should be paying attention to either; both Ramsey and Tate fall short, though for different very reasons. My larger point is two-fold: 1) Ramseyism is iffier than it seems, and 2) we should be more curious about why the young are so drawn to Tate. The controversy deserves a deeper dive, in addition to a few thoughts on what all this has to do with chivalry.

Rufo’s advice comes in the context of a larger conversation, which was driven by his previous claim that promising career opportunities are available for young men at the local Panda Express or Chipotle. It’s the kind of comment that shows the ever-widening divide between older bootstrap conservatives who think no obstacle can stand in the way of personal initiative and younger disaffected rightwingers (not conservatives, because there’s so little left to conserve) who think the bootstrappers are still living in 1985. The context matters in making sense of the Ramsey-Tate issue.

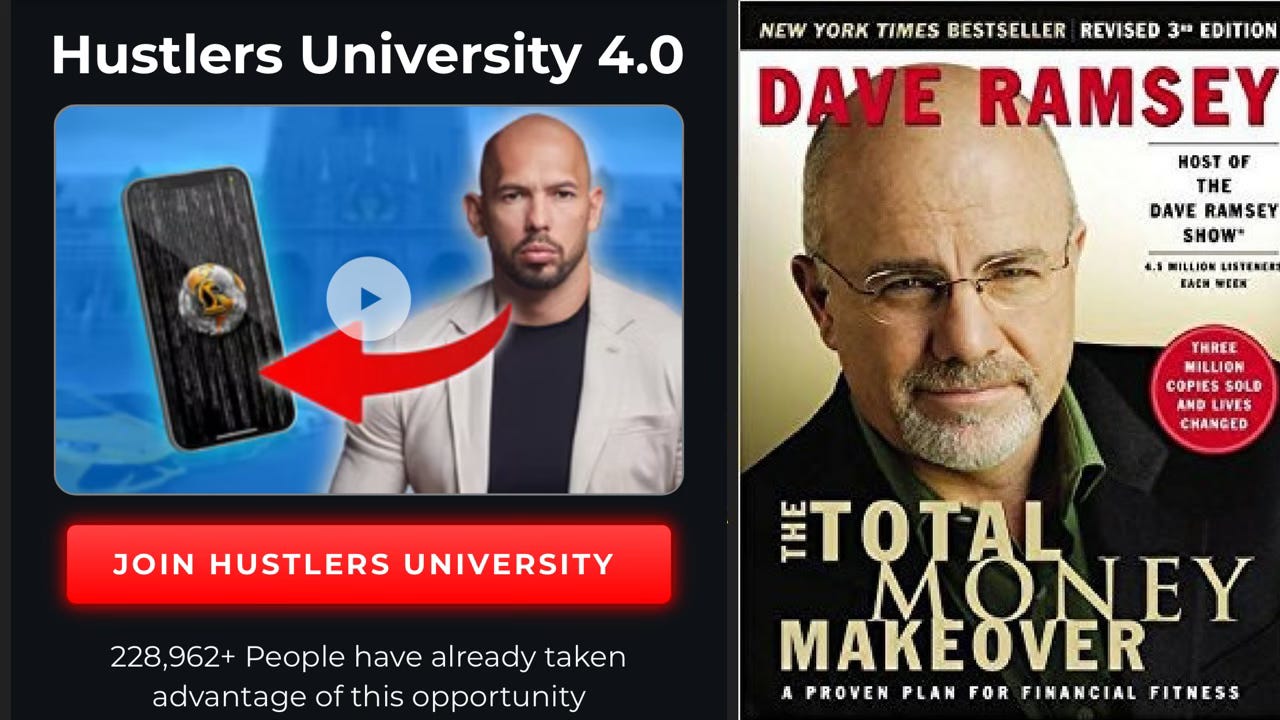

At first glance Ramsey and Tate appear to be as different as two men can get: one is a pious Protestant preaching a message of thrift and the other a criminal preaching a vision of excess and indulgence. The more I think about it, though, the more I see them as different sides of the same coin, or one as the comeuppance for the other, or both.

The Same Coin

Where does one start with Andrew Tate? I don’t follow his project closely, but here’s what I know about him. In addition to a questionable sense of style (tight shirts buttoned up only to the sternum, something you’d usually see from an Only Fans girl showing off her cleavage) and a strange formula for posting (lots of CAPS-LOCK, lots of calling people “massive gay pussies”), he has some sort of criminal record which he claims is unjust but also very skillfully plays up. He once was a professional kickboxer, but he got his start as an “influencer” with a digital pimp service, using webcam girls to pump lonely chumps for money. This scam gave him the capital to sell his own lifestyle while doing some 103 iq redpill commentary on the side. Now he runs an educational outfit called Hustler University, where students can tap into the wisdom of millionaire teachers and learn about “e-commerce, dropshipping, stocks/options, crypto/NFTs, marketing, business, fitness/nutrition, and much, much more.” This is how Tate affords the eighty-five vehicles he owns (of which he claims to only have driven twenty). The guy says a lot of outrageous things. His one quasi-virtue, as far as I can tell, is boldness—more on that later.

Against Tate, Dave Ramsey strikes a much nicer picture, which makes it safer to tout him. And he does do good in helping Americans address a real problem. But there’s something amiss, something harder to explain because everything else is supposed to scream “WHOLESOME!!!” His Amazon.com page gives a sense of it. Currently on offer are titles with a high degree of overlap and redundancy like:

How to Have More than Enough: A Step-by-Step Guide to Creating Abundance

Baby Steps Millionaires: How Ordinary People Built Extraordinary Wealth—and How You Can Too

The Total Money Makeover Updated and Expanded: A Proven Plan for Financial Peace

Financial Peace Revisited (with new chapters added from the previous version)

Smart Money Smart Kids: Raising the Next Generation to Win with Money

You can also buy workbooks and planners for some of these. The unavoidable conclusion is that Ramsey has little shame about repackaging and reselling the same idea over and over.

But wait—it’s not just the books. There’s more one his website. You can sign up for the Ramsey+ app (free and paid options). You can schedule consultations with a Ramsey-certified coach. You can become a Ramsey-certified coach yourself. You can find Ramsey-approved real estate agents, mortgage brokers, accountants, and more. This is just the start of it. There are a few dozen more ways to give Ramsey your money. At his site I get the sense that I’m in a aw-shucks version of Tate’s Hustler University. Ramsey even has his own mock-institution of higher learning: Financial Peace University. When it comes to marketing and product development and opportunism, Tate could learn much from this absolute master.

The Dave Ramsey Experience

And then there’s the show. About five or six years ago I became fascinated by the strangeness of the experience.

Caller dials in. Pleasantries are exchanged. “How are you doing, Dave?” caller says. “Better than I deserve,” Dave humbly answers. Information is given about the caller’s financial difficulties. “How much debt do you have?” and “How much do you make?” are the questions Dave asks before he runs them through his “Baby Steps,” gets them to see what they need to do, and sends them on their way.

This exchange is good. Then the next caller dials in and a strikingly similar conversation follows, but with different numbers and financial instruments. Then another call, and another—and then you realize Dave has almost the same conversation about debts and budgets and mutual funds over and over again. Ramsey’s show came to seem like a more monotonous G-rated version of Love Line—but with budgeting instead of sex and relationships. I can at least understand why people listened to Love Line or other such shows; there’s a real human element to these dramas. But the dramas of personal finance? And this was no small-time production: at the time, The Dave Ramsey Show drew an audience of 13,000,000+ listeners per week (trailing only Limbaugh, Hannity, and a few NPR productions in ratings).

Of course I’m not giving Ramsey enough credit. He formulated a simple, systematic approach to addressing a real crisis—and not just a crisis but a stain on our national honor. Teaching people how to free themselves from the snares of indebtedness is a significant contribution. A person should learn these principles (or similar ones), put them into action, and then immediately stop thinking about them, stop listening to the show, stop going to the seminars. But that doesn’t seem to be what happens. He has turned frugality into a massive empire, almost like AA for spendthrifts, and he keeps on talking about it. This combination of doing some good but also being massively shameless and opportunistic makes Ramsey a perplexing case.

And questions remain regarding the good actually accomplished. At the same time that prodigality needs to be conquered, cost-cutting is not necessarily a virtue—and certain types of cost-cutting are not just morally but even economically self-defeating. Case-in-point: canola is cheaper than butter, tallow, and lard. Canola will also cause chronic states of inflammation in your body and countless disorders which will ultimately cost far more in medications and hospital visits than you saved by choosing canola in the first place. Strict budgeteering compels us to think of cost largely in terms of what we pay at the register, when in fact far more goes into it. Life is all about getting what we pay for.

Cost-cutting also puts pressure on one to patronize the MegaChain rather than the local establishment. And so our money goes to the pockets of giant corporations far away rather than staying in the community and helping our neighbors sustain the independent livelihoods that make our town stronger. This too is a cost.

Ramsey clearly isn’t responsible for the problems of indebtedness he attempts to solve, but his solutions participate in that same economic spreadsheet-brain that has made a general mess of things in the first place. A fixation on money, on budgeting, on finances ultimately leads to a corporatized society, a dull land with endless strip malls, HR departments, team-building, idiotic jargon, and fake work.

Advice-Giving and Chivalry

And this corporatized system offers dwindling and dismal prospects to young men, a problem that Rufo and other bootstrap advice-givers are not sufficiently troubled by. “You will suck it up and work at Panda Express.” Of course two things can be true at once: a man does need to suck it up in order to brave certain difficulties in life—he always has and always will—but if he lives in an actual civilization he should also be able to count on more help than just facile, one-size-fits-all advice. The bootstrap philosophy is not just comically naive but also lazy because it excuses those with influence and power from the basic duty of trying to make life better for their people. This is what the BoomerCons miss; they think they owe others nothing. And it’s not so hard to understand why. For several decades, the economists have told us that we need not concern ourselves with this task, that everything will take care of itself if we only pursue maximal private gains and let the Invisible Hand work its magic. We’re now far enough advanced in this experiment/debacle to ask Tyler Durden’s question, “How’s that working out for you?”

One begins to suspect the Tate phenomenon is the comeuppance for letting our country fail its young men so badly.

The right response to Tate’s massive influence on the youth is alarm, maybe outrage. But that cannot be the end of it. The next step, which many won’t take, is to ask why they are drawn to him. For all his flaws, Tate has an unapologetic energy they like. But it’s deeper than that: it’s also about the dullness of a society created and ruled by money men—which not only fails to produce better heroes and better models for the young but also fails to convince them that there’s anything better than Tate’s lifestyle. We drive them right into the loving arms of a fake outlaw by giving them so little to live for but the fantasy of harems of hoes and fleets of Ferraris.

A man who thinks the solution for these young guys is simply to listen instead to Dave Ramsey is an unserious thinker.

There’s another problem with the advice industry, especially when it’s offered to those on the political right. Unlike the leftists who aim to homogenize all cogs in the machine, rwers appreciate the profound differences between people—which means generic maxims don’t work. The solid, humble Chud, whose destiny is to make trains run on time, needs different advice than the sensitive young man who is cut out for statesmanship, called to make things happen for his people. Both of these types matter, and both will require different guidance. But that’s probably a topic for a different essay.

I hope it’s clear that these meditations are pressing for those of us interested in chivalry. It’s not enough to read books on medieval heroes and lift weights and indulge in private longings to RETVRN. We want to actively recover a way of life that not only allows us to flourish as men, but actually makes human flourishing possible in the first place. CS Lewis says that this is the point of chivalry: “It may or may not be possible to produce by the thousands men [of the knightly character]. But if it is not possible, then all talk of any lasting happiness or dignity in human society is pure moonshine.”

What is the greatest threat to this ideal? Look back at Edmund Burke’s famous lament about the execution of the Queen of France and the death of chivalry, the most interesting part of which is his claim about who replaced the knight as the elite in Western society: “The age of chivalry is gone. That of sophisters, economists, and calculators has succeeded.” His line hits hard. Modern life shifts the emphasis from the nobility of the chivalric ideal to a much more small-souled concern with getting ahead. Dave Ramsey might be a really nice guy who has helped a lot of people (while also doing some damage, if I’m correct) but anyone who has built an empire on coin-counting is without a doubt an economist and a calculator. This is why I don’t join in the praise of him.

And Tate, despite being a delinquent or worse, captures a certain boldness that modern life aims to destroy in young men—with democratic propaganda, prescription medication, and a million other things. This boldness is dangerous, not just to the Regime but to everyone. You only look at Tate himself to see the downsides. But chivalry demands boldness, especially in deranged and confused times of crisis (like ours) when the action required by the moment might make a lot of people uncomfortable. There is no easy way out of the messes we have made.

On the Ramsey thing:

1) I've never been in debt, but when I needed to help a friend get out of debt, I checked out Ramsey's book from the library, read it, and then taught the method to said friend (who was stressed and not much of a reader). Friend then used the method to clear all debt. Worked a charm, neither of us spent a cent on it, and... that's probably the best way to do it.

2) But. Some things are harder than others, and it depends a lot on your personality. Back in the day, I needed to lose some weight. It was hard for me. So, I basically subscribed to *all* the paleo/lowcarb podcasts and newsfeeds. Not because they were saying new things every day, but because I needed to hear it, reinforce it, and frankly brainwash myself with it, every day, to make it stick. And... it did in fact work.

It's easy for me to squirrel away money: I'd started with the Tightwad Gazette and Your Money or Your Life back in the dark ages. Hardcore thrift. Sticking to a diet was more difficult for me, and needed a different approach. I assume that's at least part of what's going on with the Ramsey Media Empire. Some people just need to check out a book from the library. Some people need to brainwash themselves. YMMV.

Nobody's perfect. If you read the classic Your Money or Your Life, you can't help but notice that while Dominguez' personal accounting system and behavioral interventions are still as solid as ever, his investment advice hasn't been workable since the early 1990s. I think there's a certain amount of that going on with Ramsey as well: he's got a really solid system for getting out of debt... and then his investment advice (become a landlord) is basically: the thing that is eviscerating the working class and setting us up for 2008housingcrisis redux... and will someday (hopefully soon) be as out of date as "use all your spare savings to buy government bonds that yield 9%" Yay bubble investing.

Ramsey bothers me on many levels. On one level, he is a symptom of a sick society. The young shouldn't have to work two jobs just to get by. On another level, this whole idea of living on a budget strikes me as a form of loving money.

One of the main reasons for making a higher income is so you don't have to think about money so much. Just live below your means and the money piles up. You don't have to count it on a regular basis. And yes, is you choose to live super cheap, you can become a man of leisure on a Panada Express manager salary eventually. Eat those lentils!

Also, cutting up your credit cards before you have lots of savings is foolhardy. A credit line is a form of retroactive insurance. It is, of course, important to pay down your cards when you do have income. But consider the resulting headroom on the cards as part of your emergency fund.

And student loans are worth it if you get a major in a field where companies are hiring. A degree in literature or philosophy should be considered a luxury good. A degree in accounting or engineering, on the other hand, is a true monetary investment. Stretching out your schooling to eight years to avoid a loan is dumb. The human body depreciates.

Finally, being a millionaire is no longer being rich. There has been at least a 10x in prices since Thurston Howell III was stranded on Gilligan's Island.