Ghastly as they are, I can’t help but wonder whether the changes made by Peter Jackson and company to The Lord of the Rings are unintentionally perfect—because they always weaken the story and thus highlight the superiority of JRR Tolkien’s vision.

Near the top of that list of changes is the unmanning of Aragorn son of Arathorn. In Tolkien’s books he’s the ideal king, but the ladies who wrote the script had a more democratic hero in mind, a reluctant and “relatable” fellow who needs some cheerleaders to help him get over his anxieties about repeating Isildur’s mistakes. “Put aside the Ranger,” Elrond tells him in the movies. “Become who you were born to be.” The real Aragorn needs no such coaching; his Rangering is part of the plan, not a weak-kneed avoidance of destiny. Perhaps the executives and pollsters at New Line Cinema thought this change somehow gives the character a “dramatic arc,” but I never bought movie-Aragorn’s conversion from uncertain to kingly, nor am I swayed by the argument that it was necessary to compress Aragorn’s backstory for run-time.

What’s lost in this updated version of the character is magnanimity, great-heartedness. “A person is magnanimous,” Josef Pieper writes, “if he has the courage to seek what is great and becomes worthy of it.” In many cases, magnanimity compels a man to seek influence and power. Tolkien’s Aragorn is born to rule, and he knows it. Surely this will register as presumption to the lame focus-group morality of our day, but it’s only presumption if the seeker is unfit for office—someone like Lobelia Sackville-Baggins. It’s not presumption when the man is descended from kings and possesses the towering virtues that are required.

Even the possibility of such a man mostly escapes the modern understanding. You see this every time someone mouths something like, “Those who seek power are not worthy of it” or “The only person fit to rule is the one who would never want to.” Such cliches—even if they contain some wisdom—miss the larger point and reduce the range of possible rulers to a) power-hungry maniacs and b) soft men who doubt themselves. Nothing in between. The cliches ignore the possibility of a man who is worthy, who will rule well, and who is needed by his people.

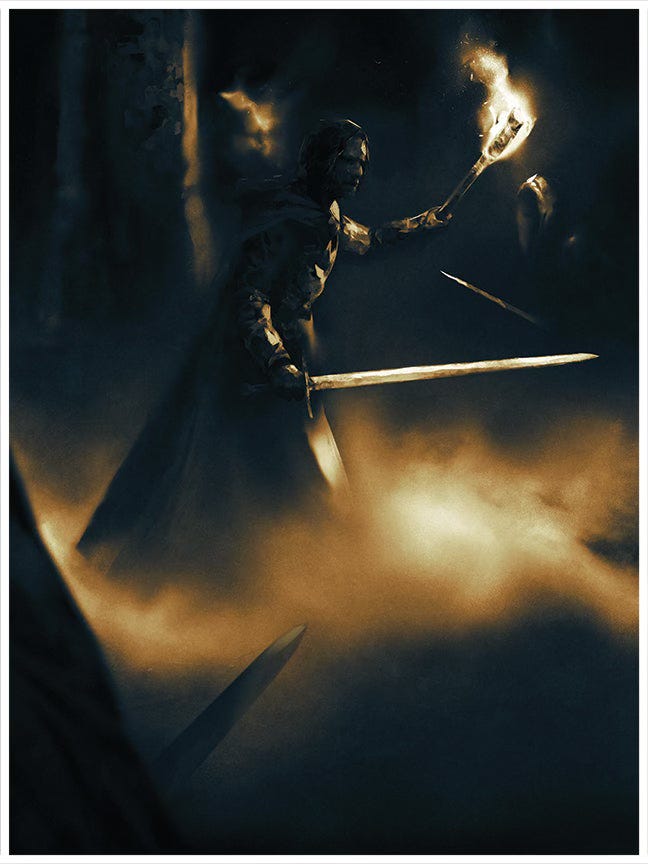

Aragorn shows the extent of his worthiness when he leads his men (and dwarves and elves) through the Paths of the Dead, a march which brings some of them to the limit of what they can endure. For the true king the challenge is not just to summon the spiritedness he himself needs for dangerous endeavors, but also to supply courage to those needing to borrow some. “Follow me,” he says. “Then Aragorn led the way,” the narrator tells us, “and such was the strength of his will in that hour that all […] followed him.”

In case the reader missed it the first time, the narrator repeats himself a few pages later: “He led the company forth upon the journey of greatest haste and weariness that any among them had known, save he alone, and only his will held them to go on.” (I love the part about Aragorn alone knowing this kind of darkness. A man like him doesn’t just presume, but tests himself and prepares for his moment.)

If the audience missed it again, Gimli later repeats the point when he confesses his own terror on the Paths: “I was held to the road only by the will of Aragorn.”

Tolkien isn’t the kind of careless story-teller who repeats himself unnecessarily. With these repetitions he wants to emphasize something crucial: the true king is a monument to heroic magnanimity and a man in whose presence others are strengthened and ennobled. He makes all the difference. Without him, the expedition halts and hope is lost. This is precisely the kind of man you want on the throne—and one who doesn’t bother with fake performative humility.

But Jackson and company seem to miss the point—they show less interest in Aragorn’s greatness than in the minor laughs that can be scored by Gimli’s comedic frightfulness.

Then there’s the Palantir scene, the single best demonstration of the difference between book-Aragorn and movie-Aragorn. Tolkien has his hero strike a blow to the heart of the Enemy by showing himself and his sword in the stone. It’s not simply bravado (though that wouldn’t be the worst thing either); it’s also strategy, and it prompts Sauron to make an unforced error in attacking Gondor too soon. When Gimli rebukes Aragorn for running this risk, the future king reminds the dwarf, “You forget to whom you speak.”1

What does Jackson do with this? His theatrical version deletes the Palantir scene altogether. One of the most rousing scenes in the story is simply cut. Worse, in an extended version the scene is altered so that Sauron imposes his will and causes Aragorn to stagger back and drop the stone in defeat. It’s hard to imagine a more unnecessary alteration. Aragorn’s big W is turned to a pitiful L, and a crucial development in the larger war is changed—all because the screenwriters wanted to remake the hero in their own image and likeness. Though they plan to build him up eventually, it’s only on their own terms, after sufficient self-doubt has been demonstrated.

The real Aragorn, rather than cowering in terror at the possibility of repeating his ancestor’s mistakes, seeks to fix them: “It seemed fit that Isildur’s heir should labor to repair Isildur’s fault,” he says. Though he knows better than to take the ring—which promises only unnatural, false power which ultimately destroys a man—he wants and seeks the real power of the crown, and he makes himself worthy of it. This act requires an assertion of will that is beyond the understanding of contemporary moralizers: the hero knows his people need him, so he’ll do what needs to be done—as magnanimity requires.

By gutting this character of his great virtue, Jackson and company unintentionally help the viewer appreciate what Tolkien was going for.

He does add a touch of friendliness and warmth to his rebuke, so that it’s not all imperiousness. But it’s crucial to note that he thinks it worthwhile to correct Gimli and assert his claim.

Excellent essay. Jackson’s Trilogy have been my favorite movies for my entire life, but I’ve noticed an interesting change over the past few years as I’ve intentionally reread the books more times: with every watch and read, I love the books more and like the movies less. The more I understand who the characters are who Tolkien wrote, the less I like their depictions in the movies.

I think only Sam and Gollum are comparable between the two with Gandalf also mostly being well done. EVERY other character is altered to the point of being unrecognizable between the two mediums. And this is the true failure of the movies, not the plot changes (elves at Helm’s Deep). Great job breaking down this aspect of just one of those character changes.

I think the greatest virtue the movies have is how thoroughly they instill a love for LOTR in kids. But like holding hands with a girl for the first time, it’s only a pale shadow of the love that can grow if they really get to know her.

Fantastic! I need to reread the series. I missed this before.