Be Careful Reading Books About the Middle Ages

A Cautiously Favorable Review of The Greatest Knight by Thomas Asbridge

I’ve learned that we must be careful reading books about the Middle Ages. Only a few historians are interested in trying to understand these strange, hierarchical, and devout times—and those who aren’t interested prefer instead to scold the medievals for failing to meet modern standards of democratic tolerance and consumer affluence. Dismissals of the people of the past are much easier than real investigations.

Whatever their failings, the medievals nevertheless had the energy to pursue projects and enterprises on a scale that should astound us. Russell Kirk wrote that "Human activity reached its point of greatest intensity in the Middle Ages, with the Crusades and the cathedrals; since then, true vitality has been waning rapidly.” It’s enough to make one wonder whether the bias and propaganda against the medievals doesn’t have a note of jealousy to it. They gave rise to a great civilization, which we have been unable to keep.

This makes selecting books about the Middle Ages a little tricky. There are some good ones out there, but they are rarer than they should be.

Enter Thomas Asbridge

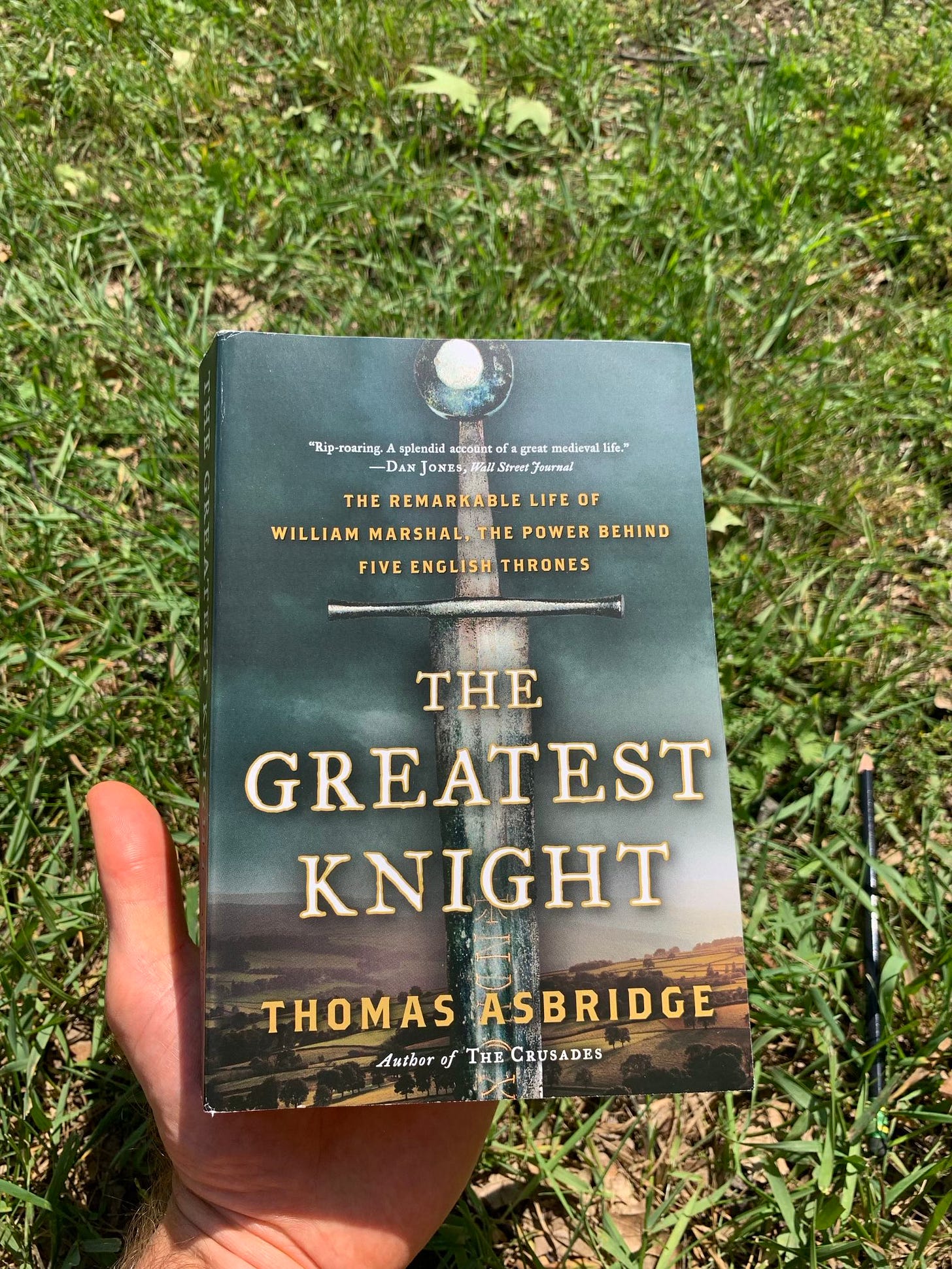

The Greatest Knight by Thomas Asbridge—a life of William Marshal (1147-1220)—offers a case study in the difficulties of studying the Middle Ages.

Marshal is an all-timer. He served five Plantagenet kings, became guardian of the realm after the death of John I, saved the dynasty in its darkest hour at the Battle of Lincoln, dominated the tournament circuit, and rose from humble origins to become the most powerful man in England and one of the greatest knights who ever lived. For some he is the greatest—thus Asbridge’s title. He is the kind of hero who deserves a fair treatment in popular biographies.

I had heard good things about Asbridge’s work—but upon receiving it was immediately underwhelmed to see a blurb on the front cover from Dan Jones, a debunker historian. I stopped reading Jones’ history of the Plantagenets, and threw it aside, when the author showed more interest in cataloguing Richard the Lionheart’s illnesses on Crusade than his exploits and implied that the great man’s real skill was in propaganda. It was disqualifying.

Early in his own book Asbridge shows similar debunking tendencies, including a flair for the use of skeptical scare-quotes. Like: “Through the twelfth century, there was a strong expectation that warriors would participate in a Crusade, mirroring the ‘glorious’ achievements of their forebears … In time, William himself would feel the call of this ‘higher cause.’” It's not at all clear whether Asbridge is quoting from The History of William Marshal or some other source—the endnotes give no indication—or whether he’s winking to cynical readers to signal his doubts about glorious achievements and higher causes. Later Asbridge titles one of the sections “A ‘hero’ rises.” As for The History of William Marshal—the delightful biography commissioned by Marshal’s son shortly after his death—Asbridge questions the work and the motives of its author. Of course a historian is supposed to question. But does he do so as an admirer of the hero and the medieval sources, or is he an eager fact-checker? For the first third of his book, it was not clear whether Thomas Asbridge even likes William the Marshal—he calls William “resolutely acquisitive, devious, proud, and even preening” and refers to his “instances of prideful self-promotion and ceaseless materialism”—and I got to wondering whether the title of Asbridge’s book was some sort of bait-and-switch to catch people who wanted a heroic history but instead were getting an ironic one.1

If that had been the case, his book would be a work of academic evil. Thankfully, it isn’t.

Asbridge changes tone midway through, cooling it on the debunking and showing that he actually does admire Sir William. And this change of tone helps Marshal-enjoyers and hero-worshippers open their minds to a couple corrections to the man’s legend. Two instances stand out.

The first is Asbridge’s challenge to the lovely story recounted in The History of William Marshal about the knighting of Henry the Young King, Henry II’s heir apparent who was crowned while Old King was still king. According to the medieval chronicler, the Young King’s retinue was unhappy that he hadn’t yet been dubbed—especially since he was about to go to war against his father. (Theirs was a family in which familiar wars were regular. More on that shortly.) A leader of men must be properly knighted before marching off to fight, so the Young King declared the ceremony would be performed by “the finest knight who ever was and is and will be, who has done and will do more deeds than any.” He meant William, his martial tutor. It was a remarkable choice because most aspiring knights angled to be dubbed by the most high-status man possible, and William was not yet the towering historical figure we now know him to be. He was hardly the obvious choice: “Yet the Marshal owned not a single strip of land,” the chronicler writes. “All that he had was his chivalry.” To his credit, the Young King understood what William Marshal was about.

But Asbridge makes a concise case that this probably didn’t happen. “It would have been very unusual for the young royal not to undergo a dubbing ceremony before his own coronation,” he writes. More importantly, “a well-placed contemporary recorded that Henry was indeed knighted by his father’s hand” a few years earlier. It’s a bit like a punch to the gut for readers like yours truly, but the student of history needs to be able to absorb such blows, and Asbridge pulls it off tactfully and not at all gleefully.

Another concern involves Marshal’s renown as a champion of the tournament circuit—achieved, Asbridge argues, with foxlike guile and not just leonine valor. Observing the success tactics of Philip of Flanders (basically: holding back from the fray until other competitors have expended energy and then entering at an opportunistic moment), William encouraged his and the Young King’s team to imitate it. Asbridge’s source for this is The History of William Marshal itself. So really it’s not even a case of debunking, but of reading closely.

William’s strategy raises difficult questions about the boundary between strategic prudence and mere cunning. I’ve argued elsewhere that chivalry and the virtuous life require us to play for keeps: the point is not simply to lose with grace while congratulating yourself for never getting your hands dirty; the point is to meet the challenges of the moment and to triumph—without losing your soul in the process. In this case, the deeper problem might be the tournament itself, or those like Philip of Flanders who had previously disgraced it with this cunning approach. If anything, Asbridge uses this episode to praise Richard the Lionheart’s priorities: while his brother the Young King and William were traveling through France in search of tournament glory, young Richard was busy subduing the barons of Aquitaine and gaining the skills that would make him a legend on the Third Crusade. He had more important things to do and he would go on to be the greatest man of the era.2

A Hero Rises—With No Quotation Marks

Thankfully the Marshal’s renown is built on more solid claims than just knighting the Young King and winning renown at the tournaments. It’s built on loyal and extraordinary service to the Plantagenet dynasty. Having cut William down to size, Asbridge builds him back up in the final chapters of his biography.

It’s no easy thing to serve the House of Plantagenet loyally, given their tendency for familial warring. Not metaphorical war but literal war. First, Henry the Young King took arms against his father. His brothers joined in. His mother joined. This war ended with Henry II triumphing and taking his own wife prisoner, where she would remain for years. Then Henry the Young King made war against his brother Richard. And Richard, when his own turn came as heir to the throne, also made war against his father. The point is that a servant of the dynasty must proceed carefully—because being on the wrong side of these can mean disaster.

William settled upon a simple and instructive policy: loyalty is best. Simple doesn’t mean naive. Our loyalty must be informed by prudence, properly ordered, and not blindly given to those undeserving of it—but at the same time it won’t do to deconstruct the virtue like self-impressed Redditors or sophisticated HBO screenwriters who delight in fringe cases and exceptions. Marshal was a ride-or-die kind of man. And his loyalty was to be tested. Near the end of Richard the Lionheart’s war against the Old King, as Henry’s fortunes waned and his health faltered, the pressure on William to abandon him must have been immense. Adding to the desire to not find oneself on the losing side, William had everything at stake after Henry had promised him the hand of a young, beautiful, and very rich heiress. When Richard finally triumphed over his father, he would punish those who took his father’s side—or so William figured. This meant William would lose big. But he stayed loyal to the Old King.

And he was rewarded for it! Rather than punishing William, Richard gladly welcomed him into his own service after Henry II died—exactly the kind of man he wanted and needed now that he was king. Not only did he uphold his father’s promise to William about Isabel of Clare—he went further and actually delivered on the promise. It’s an excellent lesson in how loyalty pays. Richard, by the way, was less impressed with and less generous toward those who abandoned Henry to join the winning side.

William would have other difficult decisions coming up. After the death of Richard in 1199, King John I's reign was so disastrous that the majority of English barons turned against him and made common cause with the King of France: in return for France’s aid in invading their country, these rebel barons would accept Prince Louis as their king. All that stood in the way of the rebellious barons and Prince Louis was William the Marshal and the small coalition he led.

The stakes were stratospheric, politically and personally. If William lost, England would be ruled by foreign kings, and the earldom, the renown, and the legacy William had fought all his life for would be taken from him and his heirs. But William on some level must have felt that he owed it to the family that gave him the opportunity to rise from obscurity to such heights. The moment of truth came at the Battle of Lincoln in 1217, when William the Marshal led a cavalry charge against the rebel barons and their French allies. He was so excited that he almost forgot to don his helmet beforehand, and he rode so hard at the enemy that he broke into their lines three lances deep. It was a turning point in English history. The best part is that William was seventy years old!

Asbridge tells William’s story admirably well, but near the end he taints his own narrative with a dash of contemporary cynicism about the hero’s motives. He writes: “William’s capacity for steadfast loyalty might be laudable, but it was also self-serving, in that it safeguarded his good name and allowed him to avoid the potent stigma of public shame.” Enlightened people seem to think that virtue is something that sounds nice and “might be laudable,” but is only worthwhile if it pays. The medievals understood things differently, daring to build a civilization in which personal and moral excellence were better integrated with the common good—rather than fully compartmentalized. Whether they succeeded is another question, but they at least wanted to encourage virtue and not snicker at it.

Only the best historians are capable of grasping this—and Asbridge, as talented as he is, falls a bit short. Like I said, we’ve got to be careful in reading about the Middle Ages.

In the opening pages, The History of William Marshal warns us against debunkers: “Anyone with a worthy subject should see he treats it in such a way that, if it starts well, it's carried through to a good conclusion—and that it chimes with the truth, irreproachably; for some are inclined to undertake such tasks with lesser intentions: they just want to run men down! And what is it that drives them? Envy—whose tongue, prompted by its bitter heart, can never stop sniping; it resents any sign of outstanding goodness.”

Asbridge’s narrative is energized whenever Richard is involved. I don’t remember a supporting character stealing scenes in a biography the way Richard does in this one.

"Only a few historians are interested in trying to understand these strange, hierarchical, and devout times—and those who aren’t interested prefer instead to scold the medievals for failing to meet modern standards of democratic tolerance and consumer affluence."

So that's why so many characters in Medieval-period novels and films wave the Magna Carta around like its the Bill of Rights. 😀

I knew next to nothing about William Marshal before I found this book at the public library. I liked it enough to buy it, and next year it’ll be required reading for my oldest two children.