This month’s selection for the Chivalry Book Club is the first half of Josef Pieper’s The Four Cardinal Virtues—on prudence and justice. (Courage and temperance will follow next month.) This is one of those books that I aim to revisit every few years—it’s studying again and again.

From my writeup on Pieper’s work from my Chivalry Reading List, Part II.

What I love about chivalry—even more than the history, horses, weaponry, aesthetics, and energy—is the framework it provides for understanding virtue.

This was something I needed help with as a young man: I heard little talk of virtue in my formative years, and what I did hear was lame. Modern usage has turned virtue into mere niceness and prudery. Prudence has been reduced to cowardly evasiveness, meekness to weakness, temperance to portion control. People are called “brave” for supporting very safe and fashionable political causes and reading titles from the “BANNED BOOKS!" table at public libraries and Barnes & Noble. If we were brainstorming ways to undermine human excellence and guarantee that men grower weaker with time, we could do no better than to confuse the language of flourishing and make it sound pathetic. Why would a red-blooded man even try?

True virtue is about excellence. The classical and medieval traditions—which produced more impressive men than ours—were obsessed with virtue and with pursuing man’s ultimate potential. The English word traces back to virtus, Latin for “moral strength, high character, goodness; manliness; valor, bravery, courage in war; excellence, worth.” “Virtue is a perfection,” writes Thomas Aquinas, “and by this we are to understand the perfection of a power.”

The writings of 20th century German philosopher Josef Pieper should begin to cure the modern reader of all misconception on the subject. The Four Cardinal Virtues presents the interlocking nature of prudence, justice, courage, and temperance, the virtues on which the good life “hinges” (cardinal coming from the Latin for “hinge”) … Pieper’s books hit a difficult mark: both deeply philosophical and deeply practical, showing how clear thinking serves good living.

Though these titles are accessible, they aren’t always easy—especially Pieper’s meditations on prudence at the beginning of T4CV. For those wanting to start a little lighter, his Brief Reader on the Virtues of the Human Heart is a good option.

My plan is to post about T4CV throughout the month and then host a discussion on Monday, June 2 for patrons and backers. Please email sonofchivalry@protonmail.com if you’re interested. The book is available online.

Reading Notes and Questions

Introduction

In his introduction, Pieper explains why virtue ethics matters: “It is true that the classic origins of the doctrine of virtue later made Christian critics suspicious of it. They warily regarded it as too philosophical and not Scriptural enough. Thus, they preferred to talk about commandments and duties rather than about virtues. To define the obligations of man is certainly a legitimate, even estimable, and no doubt necessary undertaking. With a doctrine of commandments or duties, however, there is always the danger of arbitrarily drawing up a list of requirements and losing sight of the human person who ‘ought’ to do this or that. The doctrine of virtue, on the other hand, has things to say about this human person; it speaks both of the kind of being which is his when he enters the world, as a consequence of his createdness, and the kind of being he ought to strive toward and attain to—by being prudent, just, brave, and temperate. The doctrine of virtue, that is, is one form of the doctrine of obligation; but one by nature free of regimentation and restriction. On the contrary, its aim is to clear a trail, to open a way.”

Book 1: Prudence

One of Pieper’s favorite themes is the hierarchy of the cardinal virtues. Prudence comes first because prudence is knowledge of the good and how to realize it. Justice comes next because it is prudence put into action, the doing of good, giving to others what they are owed. Courage follows because it protects our ability to know and do good from the greatest threat to it: the fear of danger and death. Finally temperance finishes off the list because it protects our ability to know and do the good from a lesser but still formidable threat: attachments and pleasures. “The whole ordered structure of the Occidental Christian view of man,” he writes, “rests upon the preeminence of prudence over the other virtues.” In order to do good, you must first have knowledge of the good and how to make it a reality.

Though the virtues are hierarchical, they connect and serve each other. Prudence helps us to know when a risk is worth taking, and courage helps protect judgment from the fearfulness that can cause us to lie to ourselves. Thus the Lewis quote: “Courage is not simply one of the virtues but the form of every virtue at the testing point, which means at the point of highest reality.”

Prudence dictates that there can be no definitive step-by-step manual for how to proceed in whatever situation. The point is that you need to exercise judgment. Which means you need to develop judgment. And you need to keep your eyes open for the opportunities that arise and disappear from moment to moment. If you would be a truly free man and a man of agency—as opposed to a slave, a follower, a mass man—there is no escape from this requirement, no outsourcing your decisions to some authority.

An incredible metaphor on living the good life: “The man who does good follows the lines of an architectural plan which has not been conceived by himself and which he does not understand as a whole, nor in all of its parts. The architectural plan is revealed to man from moment to moment. In each case he sees only a tiny segment of it, as through a narrow crack. Never, so long as he is in the state of ‘being-on-the-way,’ will the concrete architectural plan of his own self become visible to him its rounded and final shape.”

Pieper has some implied instructions on how to grow in this virtue, which I’ll lay out later—along with examples of prudence that strike me as worth studying.

Book 2: Justice

This book provides excellent clarity for our very confused ideas about “rights.” In sentimental liberal democracy, everything under the sun becomes a right: healthcare, college education, abortions, reassignment surgeries, etc. Actual rights are something which if withheld from a man do damage to the withholder. Pieper writes: “That something belongs to a man inalienably means this: the man who does not give a person what belongs to him, withholds it or deprives him of it, is really doing harm to himself.” He does damage because man is made in the image and likeness of God and thus owed certain things. But those are limited, and they require knowledge of what, exactly, a man is. It might be a nice idea to provide taxpayer-funded health care for all citizens—but a nice idea is different from a right.

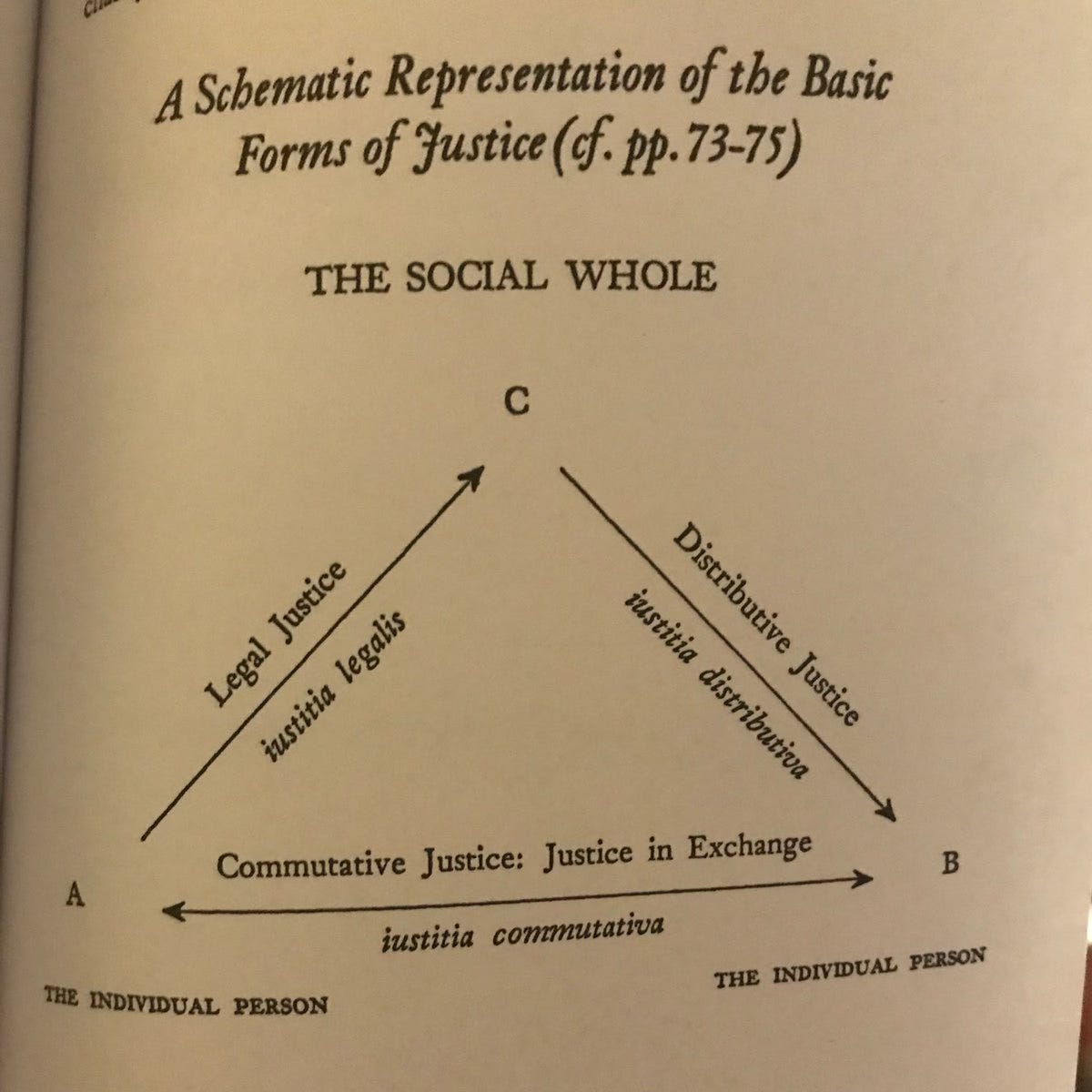

Another problem with the discussion of justice is that there are three different kinds. There is something owed: a) by society to the man, b) by man to the society, and c) by man to another man. We seem to have collapsed it all into the first, speaking only of what goodies the individual is owed by society—which is a good way to make you hate the virtue.

There’s much more to say, but I’ll save it for later posts and for our discussion.