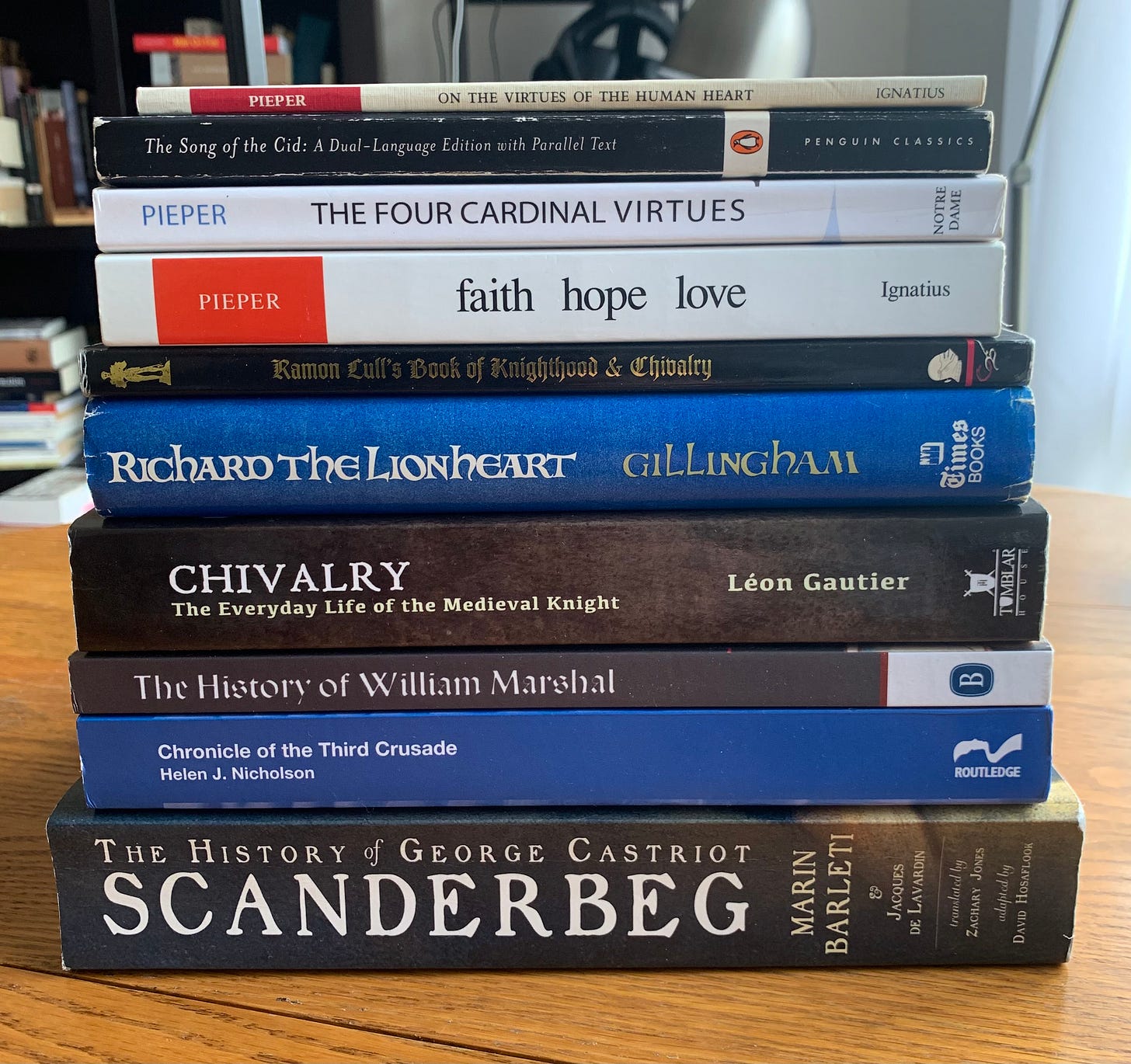

Continuing the list of must-reads. See Part I if you haven’t already.

The Four Cardinal Virtues, Faith Hope Love, & A Brief Reader on the Virtues of the Human Heart by Josef Pieper

What I love about chivalry—even more than the history, horses, weaponry, aesthetics, and energy—is the framework it provides for understanding virtue.

This was something I needed help with as a young man: I heard little talk of virtue in my formative years, and what I did hear was lame. Modern usage has turned virtue into mere niceness and prudery. Prudence has been reduced to cowardly evasiveness, meekness to weakness, temperance to portion control. People are called “brave” for supporting very safe and fashionable political causes and reading titles from the “BANNED BOOKS!" table at public libraries and Barnes & Noble. If we were brainstorming ways to undermine human excellence and guarantee that men grower weaker with time, we could do no better than to confuse the language of flourishing and make it sound pathetic. Why would a red-blooded man even try?

True virtue is about excellence. The classical and medieval traditions—which produced more impressive men than ours—were obsessed with virtue and with pursuing man’s ultimate potential. The English word traces back to virtus, Latin for “moral strength, high character, goodness; manliness; valor, bravery, courage in war; excellence, worth.” “Virtue is a perfection,” writes Thomas Aquinas, “and by this we are to understand the perfection of a power.”

The writings of 20th century German philosopher Josef Pieper should begin to cure the modern reader of all misconception on the subject. The Four Cardinal Virtues presents the interlocking nature of prudence, justice, courage, and temperance, the virtues on which the good life “hinges” (cardinal coming from the Latin for “hinge”). Faith Hope Love presents a very unchurchy case for the theological virtues, including a rousing description of the tandem nature of magnanimity and humility. These virtues are not either/or but both/and. Pieper’s books hit a difficult mark: both deeply philosophical and deeply practical, showing how clear thinking serves good living.

Though these titles are accessible, they aren’t always easy—especially Pieper’s meditations on prudence at the beginning of T4CV. For those wanting to start a little lighter, his Brief Reader on the Virtues of the Human Heart is a good option. Also, heads-up: The Four Cardinal Virtues is a selection for the Chivalry Book Club in the upcoming months. We’ll discuss the chapters on prudence and justice in May, and the chapters on courage and temperance in June.

The Song of the Cid

The Song of the Cid is the national epic of Spain, chronicling the great deeds of Rodrigo Diaz de Vivar, also known by the honorific given to him by the Moors (Sayyid, "the Lord/Master” —> Cid). It’s almost a proto-cowboy tale, only Iberian and medieval: after he is unjustly banished from Castile, the hero must make his way in the dangerous frontiers; he must defeat enemies and bring order and justice to a wild land.

The chivalric virtues are on full display in El Cid: prowess, courtesy, honor, generosity, loyalty, and faith. He repeatedly performs wonders with a sword and routs foes; he inspires devotion in his followers and returns their loyalty; he loves and serves the Lord (and also offers prayers of thanksgiving even for the dangers he’s about to face). The song shows that the virtues are not just moral niceties—they form character, and shape destiny. They are for doing good in the world, and they help El Cid achieve the unthinkable in carving out an independent Christian realm in Moorish Spain and defending it against overwhelming enemies.

Scanderbeg by Marin Barleti

This book is an investment, both of time (684 large pages) and money (currently $39.99 on Amazon). But if you were as moved as I was by Ibrahim’s chapter on Scanderbeg in Defenders of the West, this classic 16th century biography of the Albanian hero is time and money well spent.

From my essay on Scanderbeg:

Two questions struck me as I learned of the life and deeds of George Castrioti (1405-1468), also known by the title given to him by the Ottoman Turks: Scanderbeg. The first question is, How is this guy real? He lived an impossibly epic life—taken from his family as a boy and forced to become an Ottoman soldier, only to revolt against his masters years later, return to Albania, and lead a glorious resistance against the Ottomans. According to Marin Barleti, Scanderbeg’s great biographer, the hero won no fewer than twenty-five battles against the Turks over the course of his career and suffered maybe one defeat, or draw, depending how you score it. Gibbon estimates that Scanderbeg personally killed 3000 Turks. Another historian claimed that “The exploits even of the renowned paladins of the Crusades, whether Godfrey or Tancred or Richard or Raymond, pale to insignificance by similar comparison.”

Richard the Lionheart by John Gillingham & Chronicle of the Third Crusade (Edited by Helen J Nicholson)

Of the great heroes of Christendom, Richard I of England holds a special place in my heart. Even just learning that there was once a king called The Lionheart was a powerful experience.1 But one must be selective in reading about Richard. He, like El Cid, is strangely controversial—the target of low-energy debunking. They want to make him seem like a negligent king (“He only spent nine months in England!”) and an overrated Crusader (“Didn’t even take Jerusalem!”) and even a sexual deviant (“Shared a bed with Philip!”). So finding a good modern biography of Richard can be a little tricky.

Gillingham’s shows that Richard’s legendary epithet—probably my favorite in all of history—was well-earned. The story has epic written all over it: from Richard’s upbringing as the child of parents who literally went to war against each other, to his rise as a young warlord duke, his ascension to the throne after the death of his father, his glorious Crusade, his betrayal by his brother and others, his imprisonment, and his campaign to take back what the traitors tried to steal while he was away. Gillingham debunks the debunkers and shows the great man for what he is.

For an excellent primary source, read Nicholson’s Chronicle of the Third Crusade. The descriptions of Richard in battle read like something out of a medieval Iliad—and if they seem outlandish just remember that the Islamic sources confirm the terror he inflicted on his enemies.

The History of William the Marshal

Born in 1146, the 4th son of a middling aristocrat, William the Marshal served five Plantagenet kings (including Richard), knighted two of them, saved the dynasty in a very dark hour at the Battle of Lincoln, dominated the tournament circuit in his spare time, and rose from humble origins to become one of the greatest knights who ever lived. Some consider him the greatest. The Marshal was a real-life Lancelot—down to the rumors about an affair with the queen, except that in William’s case they were false.

This history was written in the 1220s, just after his death. It chronicles his rise to greatness and is drawn from eye-witness accounts. Beyond his prowess, the Marshal was a model of loyalty and frankness, and every aspiring cavalier would do well to spend quality time with him.

Book of the Order of Chivalry by Ramon Lull

Centuries before the Dos Equis man, Ramon Lull (1232-1316) might have been the Most Interesting Man in the World: a Christian mystic, polymath, and prolific writer who translated his own works—and previously a hard-living troubadour and knight who fought in James I of Aragon’s glorious campaign against the Moors during the Reconquista. He had led a libertine existence as a young man, until seeing visions of the Lord in 1263—after which he changed his ways. “He became,” Noel Fallows writes, “a peripatetic scholar, evangelist and missionary, an accomplished theological theorist, well-versed in biblical exegesis and rhetoric, and a prolific writer on a wealth of subjects." All this despite being basically self-taught. Lull was beatified by Pius IX in 1847.

The Book of The Order of Chivalry is one of the essential medieval sources on the code. Lull frames his instructional manual in the narrative of an encounter between a squire who gets lost on his way to a tournament and an old knight who has retired into the hermitage of a forest. The squire seeks to learn true chivalry, so the hermit-knight teaches him.

A few of my favorite of his teachings:

God of glory chose the knights because by force of arms they vanquished miscreants who labored daily to destroy the Holy Church, and such knights God holds as friends, honored in this world, and in that other, when they keep and maintain the faith by which we intend to be saved.

The office of a knight is to maintain and defend women, widows and orphans, men diseased, and those who are neither powerful nor strong … because the great, honorable, and mighty must succor and aid those who are under them.

In likewise as God has given to the knight a heart, to the end that he is hardy by his nobility, so ought he to have mercy in his heart. And so ought his courage be inclined to the works of misiacord and piety. That is to wit: to help and to aid those who are weeping, who require the knight’s aid and mercy and who in the knights have their hope.2

Chivalry by Leon Gautier

Leon Gautier presents chivalry through the lens of the chansons de geste (songs of great deeds) like The Song of Roland; he’s a literary historian attempting to piece together a picture of what a knight’s life was like from day to day. The man has a knack for bangers: “Chivalry is the Christian form of the military profession: the knight is the Christian soldier.” “‘Fight, God is with you.’ Such, in a few words, was the whole formula of Christian courage.” “Chivalry has never been, is not, and never will be anything but armed force in service of unarmed truth.”

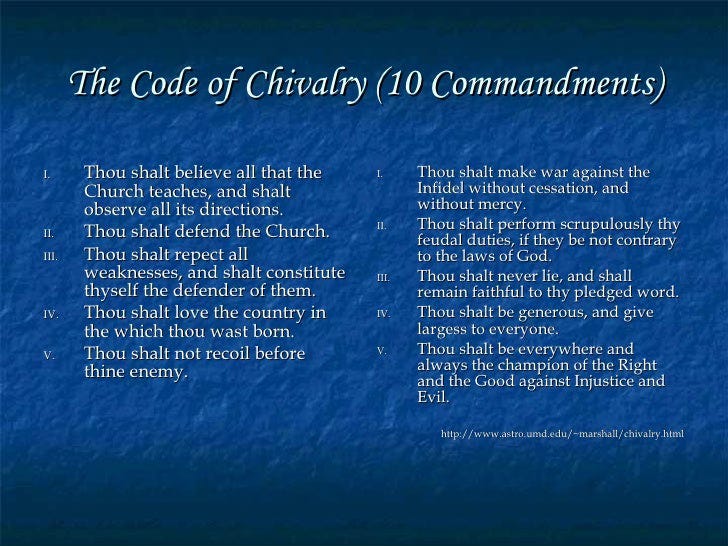

Gautier also compiles a famous Ten Commandments of the Code of Chivalry.

This might alarm some—but Gautier presents a case against Arthurian chivalry (the Matter of England) and in favor of Carolingian chivalry (the Matter of France). He’s less interested in knights riding around the countryside looking for damsels to save and more interested in the rough and devout warrior-ethos of the defenders of Christendom. I’ll write more about this soon.

Audio-Visual Bonus

Since I included books about them on this list, I should add that Dan Davis has excellent biographies on El Cid, Richard the Lionhearted, and William the Marshal, as well as Vlad, on his Youtube channel. Highly recommended.

More to Come…

Ten more books should suffice for now. Ten more to follow soon.

Not that my teachers taught me anything about him. In their cannon of heroes there was no room for a medieval warrior-king alongside the political agitators for various rights and luminaries of special interests.

These passages come from Claxton’s translation. I recently ordered a newer translation from Noel Fallows and suspect this will be a better starting point for most readers.

I have trouble only with iv... but what is a "country"? Toss off the shallow notion that the country you must give your life for is the "nation state". That is a modernist fabrication. Your country is the community into which you were born, that gave you the customs, traditions, even laws that set you on that great quest of chivalrous life to which we are engaged. To slay the Dragon may well be to slay the nation state that is our oppressor.

Great reading list. Let me suggest some chivalry-adjacent (so to speak) books: *The Myth of the Andalusian Paradise* by Dario Fernandez-Morera. A little dry-scholarly, but a good antidote to the false Christian-rube narrative about Spain. *Empires of the Sea* by Roger Crowley. A history written in dramatic fashion about Malta and Lepanto. Finally, *The Siege of the Alcázar* by Cecil D. Eby. 20th-century of course, but read and see if you agree that Col. Moscardó's leadership exemplified the principles of chivalry.