Among the heroes of Christendom who have been criminally neglected by later centuries is Fernando III of Castile and León (1199-1252). Descendant of El Cid Campeador, first cousin of Louis IX of France, and ancestor of Isabella the Catholic, Fernando achieved enough to compare favorably to all of them—yet somehow he has been lost to history. The man took back more territory from the Moors than any other Spanish monarch, never losing a battle and virtually completing the Reconquista. He proved a just and wise ruler of a growing kingdom. He was also known for his holiness—popularly called “El Santo” during his lifetime—and in 1671 he was canonized by Pope Clement X.

For a vivid snapshot of the man and his virtues, we will turn to his conquest of Córdoba in 1236.

The Soldiers

A king can often be measured by his effect on the men in his kingdom—true-hearted subjects respond to greatness.

It was a cold and rainy night in January of 1236 when a band of young knights on the frontier between Christian Spain and Al-Andalus set out to do something big or die trying. The chronicler Sr Castro de Fernandez jokes that these caballeros hardly worried about catching illness in the dreary conditions, because illness itself is afraid of such bold men! Supplied with cord and wooden ladders, they rode through the mountain paths to Muslim Córdoba, the “ornament of the world” and the “most stalwart shield and bastion against the Christians.” They had taken it upon themselves to begin the conquest of that city. What a time it was to be alive—you really could just do things.

Upon reaching the walls of an eastern district or suburb of Córdoba, the band divided in half: some would ride to the gate and wait until their companions opened it from the inside. The rest got the climbing gear ready. But the walls of that city were so high that their ladders could not reach even halfway up—so they had to tie three together and pray to God that the jerry-rigging would hold. Not a leap of faith, but a climb of faith.

Some arrangements had been made beforehand with a discontented Moor of the city, but soon the guards on night-watch discovered the knights and drew their weapons. It was time to fight. The Christians dispatched the first few, but they woke more of the garrison when they threw the slain guards over the wall. Falling bodies make too much noise. The alarm sounded. The Moors came out in numbers. What a cinematic scene must have ensued—a do-or-die struggle with a clear objective (get to the gate and open it), impediments in the way (more Muslims with scimitars arriving by the second), and the promise of glory if they triumphed (Christian reinforcements rushing in). This moment was a young knight’s chance to earn a place of honor in the history of the Reconquest of Spain.

When it was done the district belonged to the Christians. There was little time for celebrating, though: conquering a part of famous city with a small band of adventurer-knights was one thing; holding it with just a few men, and finishing the conquest, was another. So two riders were send with the message—one to the commander on the frontier and another to King Fernando himself. If the king came, they could finish this thing properly. The rider sent to Fernando, a young knight named Ordoño Alvarez de Asturias, vowed to make haste on his mission: “I will not leave my turn,” he vowed, “nor sleep on a bed, nor eat bread on a tablecloth, nor disarm until I tell this news to our good King.”

The King

King Fernando had been at court in Benavente, about 300 miles north of Córdoba, tending to the business of his kingdom and grieving his late wife Beatrice, who had died in childbirth. If anyone needed a great task to take his mind from his sorrows, Fernando was that man.

The king had just sat down to dinner with his courtiers when he received word that Ordoño Alvarez had arrived from the frontier bringing “happy and marvelous” news. With his armor muddied and his hair wet from the rain, the knight who entered the hall and kissed the king’s hand was out of place among the courtiers. But he was high in spirits as he said, “Lord, know that you are the master of the Ararquía of Córdoba.” Fernando eagerly read the report handed to him.

Ordoño Alvarez had hoped for a prompt response from the king, and Fernando would not disappoint—turning to his page and ordering that his horse be saddled. His eagerness alarmed the older members of his court. “But consider,” they said, “that it is raining hard, and the roads are in a bad state. You are risking your health, Lord, and what would become of these kingdoms without you?” It wasn’t a bad argument, but it didn’t speak to a man with so much purpose in his eyes.

Fernando answered, “What will become of them and me is always the will of God. And do you believe that it is His pleasure that, while the vassals suffer from battle and wounds, the king who should give them example is at home relaxing?” Echoing the vow of Ordoño Alvarez, Fernando said: “I tell you that I will not eat bread on a tablecloth until I do so on my own in Córdoba.”

The king rode so hard that some of his war party fell behind. They would arrive when they were able—but he needed to be in Córdoba now.

Fernando had decided that time was too much of the essence for the riders to be weighed down by provisions. They would live off the land. At one point their route brought them across a Moorish castle, and Fernando asked for the Virgin Mary’s intercession. “O most generous and powerful Queen, will thou not give me the bread that thy servants and knights need, who, for thy Son and for thee expose themselves to injury and death?”

Then Fernando's brother Alfonso pointed to the gates of the castle, out of which rode the Muslim governor and a party of servants carrying baskets of food and wineskins. The governor did not need to be told the name of the man before him. He said, “King Fernando, only you could be so brave as the place your tent so close to a Moorish castle […] I want very much to be your friend and ask you to accept these my gifts.”

Fernando gratefully accepted. “It is true that many Moors are my friends, and none of them are sorry for it,” he said. He could be a gracious enemy, but he was forceful and he was no pluralist. The point of his life was to win Spain for God. “If you are such a good friend of mine,” Fernando added, “you should give me the keys to your castle.”

The Muslim governor was taken aback. “That is impossible! I am subject of Córdoba, and the castle will not belong to you until you conquer Córdoba.”

Fernando smiled. “It makes me happy to see that you are loyal and true to your word. Thus, as soon as I have Córdoba, you will surrender them to me.”

It was one month to the day after the fall of the Ararquía of Córdoba that Fernando and his party reached their destination and ate their bread on a tablecloth for the first time since leaving Benavente.

The next morning they toured the grounds and assessed the labors before them. When they identified a bridge that needed to be captured before anything else, Fernando’s brother volunteered to lead the mission—only to have his gracious offer declined by the king. Fernando would lead the party himself. As had been the case in the dining hall of Benavente, the king was presented with well-reasoned arguments against such a dangerous course of action, and again he was unpersuaded.

“I will never place one of my vassals in a greater danger than myself,” Fernando said.

He addressed the entire assembled forces a little later and told them of the night raid that would be launched: “I shall take 200 knights and a few foot soldiers, and be assured that your nourishment will be the same as mine, and that I will suffer on my body all of the labor and wounds you will suffer […] My friends and loyal vassals—who among you has a great desire to do great things for Our Lord Jesus Christ?”

The chronicler reports:

The Moors had bad luck that night—assaulted suddenly by the silent army, cut up and beaten, with many smashed by clubs. Those who could escape fled. By the light of the sunrise, the people of Córdoba saw floating above the tower of Calahorra hora not the crescent of the prophet, but the Cross of Jesus Christ and the purple flag of Castile.

The Spaniards began preparations for the siege of the city. But ominous news arrived of the approach of a Moorish army which dwarfed their own—5,000 cavalrymen and 30,000 infantrymen under the command of Ibn-Hud. The mission was about to become far more difficult. Fernando had pulled off triumphs against numerically superior forces before, but this time he would be outnumbered forty-to-one. So the king did what he always did: took to prayer. (He often prayed so late into the night that his men worried for his health.) This time his prayers were answered with the arrival of a familiar face in camp: Ibn-Hud had sent a Christian exile from Castile—one banished by Fernando himself—to assess the strength of the Christian forces.

At first the king was outraged when Lorenzo Suárez presented himself. But the man who had been banished long ago for was not the same man who stood before Fernando now; he was eager to win the king’s favor and return to Christian Spain. Lorenzo Suárez would let Ibn-Hud believe that Fernando had a larger army than the one assembled—which was convenient enough because the Moor was eager to avoid Fernando anyways, and he had other problems, like James I of Aragon further east. Fernando was free to continue the siege.

But, again, there are always new problem just around the corner—even when you’re one of God’s favorites. Fernando’s vassals from his father’s country had fulfilled their yearly obligations and were eager to return home, just as things were getting good! There’s a long backstory of contention between Fernando and his deceased father, as well as between Castile and León, and now the letter of the law demanded that Fernando allow them to depart.

Some men are clearly operating one a higher spiritual plane than others, and it shows in the clarity and profundity of their words. When the more gung-ho Castilians were upbraiding the departed Leonese for their lack of faith, Fernando used the moment to make a devastating point: “You can see, my friends, how ugly it is to abandon the king in order to avoid hardships and return home to enjoy the comforts and leisure there. May it please God Almighty that we never do that to our King and Lord, Jesus Christ!”

They would finish the mission without the Leonese. On June 29, 1236, after a siege of several months, Fernando III became master of Córdoba. The great city was reclaimed for the Lord.

Postscript: A Discovery

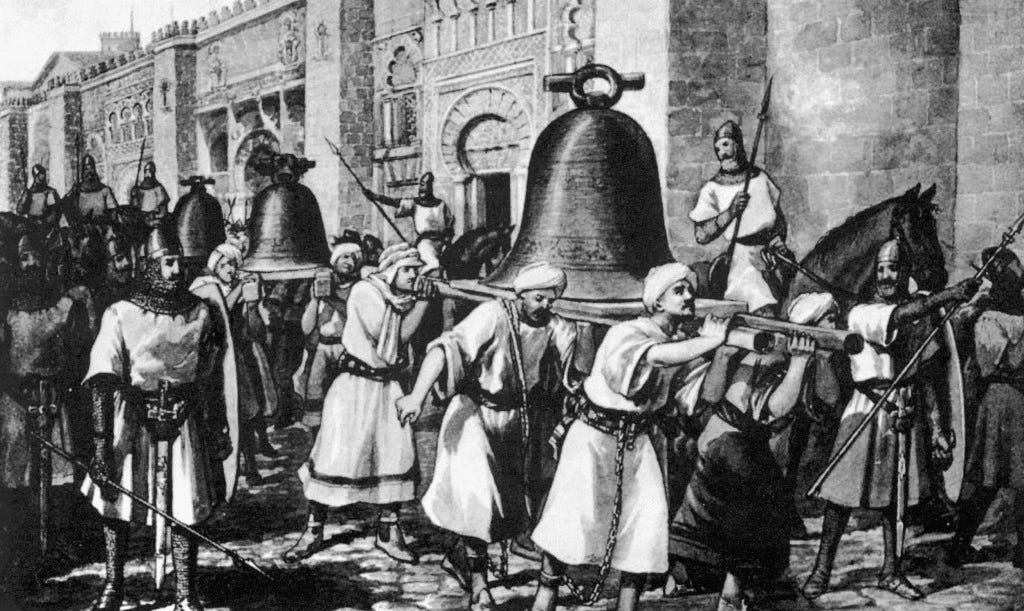

Anytime a Christian king reconquered a Moorish city, one of the first orders of business was converting the mosque into a church. A Cross was erected atop the highest minaret, and the interior was sprinkled with holy water and salt. In this mosque, the Christians discovered a surprise: the bells of Santiago de Compostela, which had been taken 250 years earlier as trophies of war by the warlord Al-Mansur and carried to Córdoba on the backs of Christian captives. But Al-Mansur, despite all the terror he inflicted on the Christians of Spain long ago—including burning Santiago de Compostela to the ground—went to his grave anxious that he hadn’t done enough to permanently stamp out the threat. He feared they would rise and retake Spain, and he was right. Fernando III was the fulfillment of his fears. He took back the great city, and many others, and when he found the bells he thought it right and just that Muslim captives should be made to return them to where they belong.

Sources:

The Life of the Very Noble King of Castile and León Saint Ferdinand III by C. Fernandez de Castro, ACJ

Saint Fernando III by James Fitzhenry

Defenders of the West by Raymond Ibrahim

What an example for today. Let us not shrink when the moment demands our attention.